Why Computers Only Have Two Fingers

Throughout history, humans have always sought ways to capture meaningful experiences or knowledge. From vivid hunting scenes etched on cave walls to wisdom carefully inscribed on papyrus, these efforts were born from a deep human need to understand the world and communicate with others.

People have long tried to faithfully capture continuously changing natural phenomena, such as sound and light. A vinyl record, for instance, captures the subtle vibrations of voices and instruments as continuous grooves etched into its surface. Similarly, traditional film cameras record the varying intensities of incoming light as continuous chemical changes on film. We call this method of capturing the world in its continuous form analog.

Yet computers, the heart of modern civilization, took a different path entirely—digital. This involves representing the vibrant, continuously changing real world using only clearly distinct values.

How can such simplicity hold the richness of the analog world? And why did computers choose this approach? Let’s explore why computers adopted digital methods and venture into the basic world of 0s and 1s. We’ll discover how these two simple numbers become the building blocks for sounds, texts, images, and virtually everything we can imagine.

How Computers Break Down Reality

Digital means breaking all information into small, discrete pieces represented by simple numbers. Each small piece becomes a fundamental unit of information that computers can understand.

Take a photograph, for example. With film, an image records continuous variations of brightness and colors. But a digital camera divides an image into tiny squares called pixels. Each pixel captures the intensity and color information of its small area as numerical values, converting the entire scene into a massive set of digital data.

Why does a computer break down reality into these digital pieces? First, digital information is clear and resilient to interference. Analog signals, being continuous, are sensitive and easily distorted by slight changes or interference. But digital information is expressed as distinctly separate states, like “on/off,” making it robust and easily identifiable, even when minor interference occurs.

Second, digital information can be handled without loss. Unlike analog copying—where repeated reproductions become blurry and distorted—digital data remains perfectly intact, no matter how many times it’s copied or transmitted around the globe. This makes digital ideal for tasks where accuracy and reliability are crucial.

But why specifically binary, using just two states—0 and 1—rather than three or four?

Computers Only Have Two Fingers

If humans use ten fingers, leading to a decimal system, you might say computers have two fingers for binary. There’s a deeply practical, hardware-engineering reason behind this choice.

Computers operate on electricity, which can fluctuate unpredictably. If signals were divided into multiple subtle levels—like “slightly on,” “medium,” and “strongly on”—precise control would become challenging. Signals weaken over distance, components degrade, and interference occurs, potentially causing catastrophic mistakes in computation.

Using just two states—“clearly high (1)” or “clearly low (0)“—ensures that even weakened or slightly noisy signals remain distinguishable. Binary thus provides a forgiving and stable foundation for reliable computing.

디지털 신호 목표값 1

아날로그 신호 목표값 5

Ultimately, binary was a practical choice by engineers to create reliable machines from inherently imperfect electrical signals.

Bits

Earlier, we mentioned that computers use two states, 0 and 1, to represent information. Each of these tiny units is called a bit. Every sophisticated task you perform with a computer involves manipulating these fundamental bits.

Bringing 0 and 1 into Reality

If computers merely stored electrical bits, they would be simple memory devices. The true power of computers lies in processing these bits to produce meaningful outcomes. But how do these 0s and 1s become meaningful?

The foundation is Boolean algebra, created by 19th-century mathematician George Boole. Boole provided a way to express logical thoughts clearly using only two values: true and false. Amazingly, 0 and 1 perfectly match Boolean logic—humans assigned “0” to false and “1” to true, enabling logical reasoning within machines.

But translating abstract Boolean logic into tangible electronic circuits required a crucial leap, made by American scientist Claude Shannon. Claude AI from Anthropic is named after him!

In 1937, at just 21, Shannon published his master’s thesis, “A Symbolic Analysis of Relay and Switching Circuits”, demonstrating mathematically how Boolean algebra could directly model and analyze electrical circuits composed of switches.

His insight revolutionized electrical engineering, making circuit design clear and scientific, effectively opening the door to the digital era.

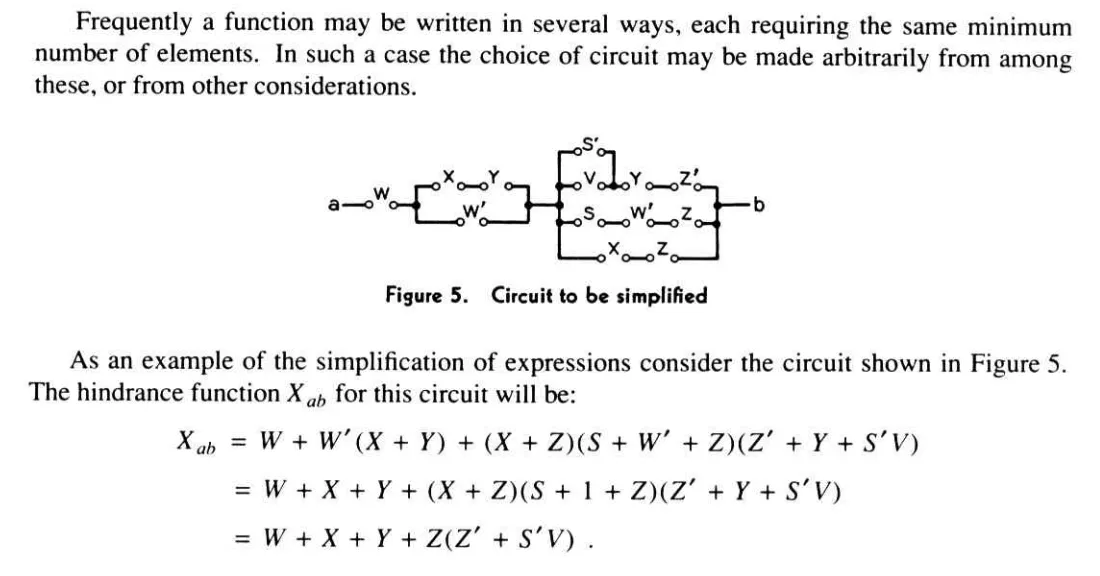

Now, let’s take this logic further into Boolean functions.

Deciding to Take an Umbrella with Bits

A Boolean function takes Boolean inputs and provides a Boolean output based on logical rules. This logical behavior is illustrated clearly by a truth table.

Consider deciding whether to bring an umbrella:

- Input A: Is rain forecasted today? (0: No, 1: Yes)

- Input B: Do I plan to go out today? (0: No, 1: Yes)

The output would be:

- Output: Bring an umbrella? (0: No, 1: Yes)

We usually take an umbrella only if both rain is forecasted and we plan to go out. Represented as a truth table:

| Bring an Umbrella | ||

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

This clearly illustrates the logical decision-making process. Computers internally use countless Boolean functions defined by truth tables for decision-making and computations.

Conclusion

We’ve explored why computers chose digital over analog, why specifically binary (0 and 1) makes sense, and how bits can represent logical true/false states. We saw how Boolean logic and electrical circuits connect, setting the foundation for logical decision-making in computers through Boolean functions and truth tables.

In the next article, we’ll delve deeper into how truth tables and Boolean functions become real-world logic gates!

You need to login to leave a comment.