If All It Does Is Math, It's Just a Calculator

Looking back at what we’ve built so far, it seems more like a calculator than a computer. In previous posts, we implemented circuits that represent numbers as 0s and 1s and perform addition and subtraction. If we represent images as 0s and 1s, we could also create circuits that can edit those images.

However, these circuits alone don’t quite feel like what we would call a ‘computer’ that we’re familiar with.

There is a fundamental difference between computers and other tools. Why don’t the circuits we’ve built feel like computers? This isn’t simply a matter of the number of functions. No matter how many functions we add—text editor, games, music player—it’s still just a “device that can only perform specific tasks.”

Scissors can be defined by their role of “cutting,” cups by “holding,” but computers cannot be defined so simply. Computers seem to have a more essential characteristic that sets them apart from other tools.

So what do we need to build to say we’ve created a computer? The goal of this series was to build a computer from scratch, but we haven’t actually clearly defined what a computer is. In this article, we’ll define what a computer is and examine how the concepts we’ve learned so far come together to form a computer.

Turing Machine: Searching for the Essence of Computation

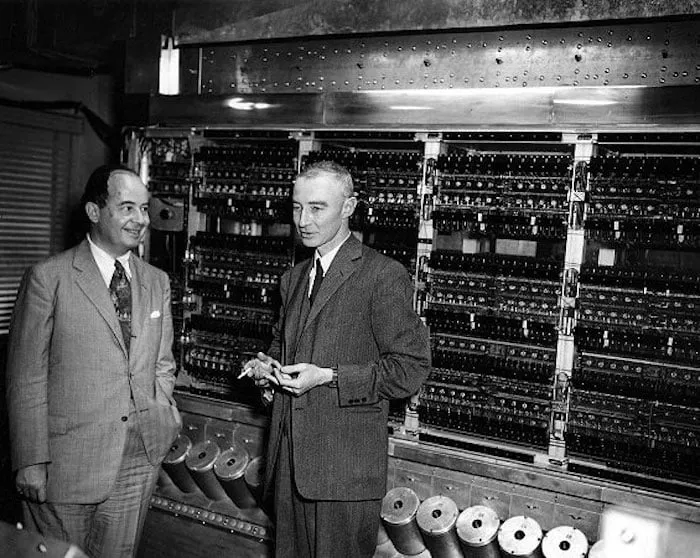

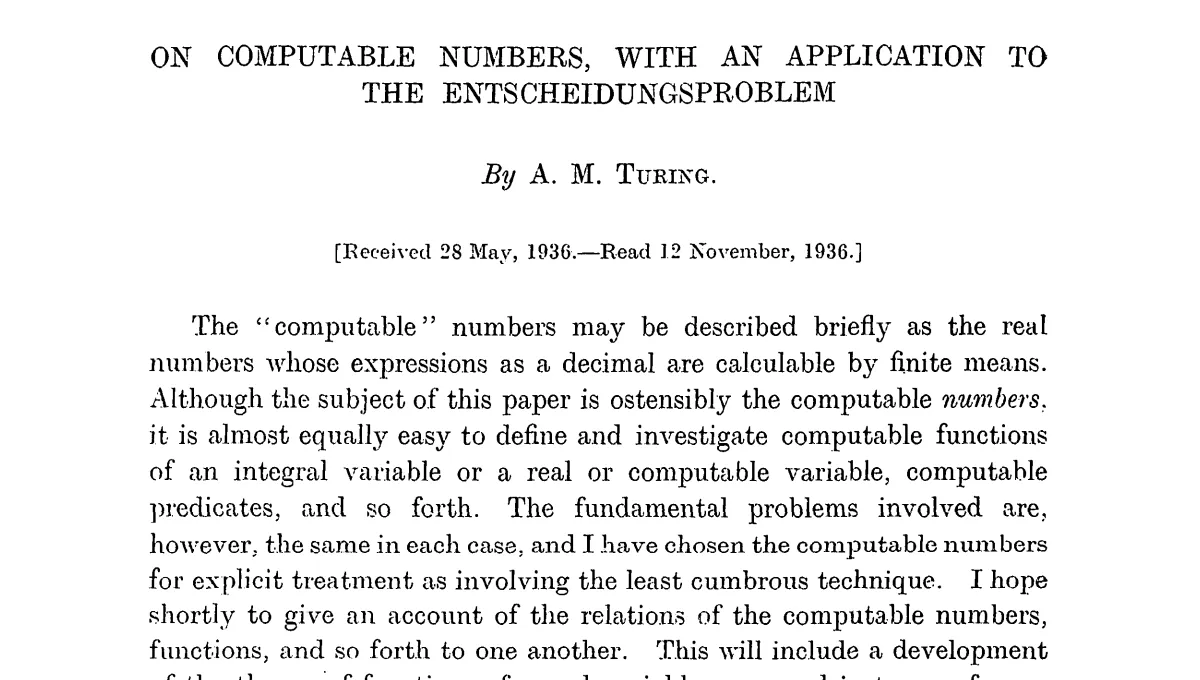

To understand the fundamental difference between computers and other tools, we need to start with one mathematician’s idea. The Turing machine, proposed by British mathematician Alan Turing in his 1936 paper “On Computable Numbers” paper, is precisely that starting point.

The background to Turing’s proposal involved an important problem in the mathematical community at the time. David Hilbert’s intimidatingly named “Entscheidungsproblem” (decision problem) was the question:

Can we mechanically determine whether a given mathematical proposition is true or false?

To solve this problem, Turing first defined the concept of ‘computation’ itself, and the result was the Turing machine.

Structure of a Turing Machine

The structure of a Turing machine is surprisingly simple. A long tape, a head that can read or write symbols on this tape, and a control unit that stores the machine’s current state and rules. That’s all there is to it. The head reads symbols on the tape and, according to predetermined rules, writes new symbols on the tape or moves the tape one position to the left or right.

Turing’s insight was that all computable processes could be expressed through combinations of these simple operations. Even complex mathematical problems or logical reasoning can be described using this model.

I’ve prepared a simulator where you can see how a Turing machine operates. The Turing machine below inverts each bit on the tape using these rules:

- When it encounters 0, change it to 1 and move right

- When it encounters 1, change it to 0 and move right

- When it encounters a blank space (_), stop working

See how a bit string is inverted through simple repeated read-write-move operations.

Tape

Control Unit

| Current State | Read Symbol | Next State | Write Symbol | Move |

|---|

Was that example too simple for demonstrating that Turing machines can express all computable processes? Below is a Turing machine that performs addition. Watch as it calculates 111₂ + 10₂ = 1001₂. If you want to understand the detailed operating principles, please refer to the source.

Tape

Control Unit

| Current State | Read Symbol | Next State | Write Symbol | Move |

|---|

As we can see, a Turing machine can perform complex calculations using a very simple set of rules. But at this point, it’s no different from any other tool. Despite creating this interesting-looking machine called a Turing machine, it’s still just a specialized tool that inverts strings or performs addition.

Universal Turing Machine

Here’s where another of Turing’s ideas comes into play. One special Turing machine can simulate all other Turing machines. This is the Universal Turing Machine.

As we saw above, regular Turing machines have fixed sets of states and rules, so they can’t perform any tasks other than what they were designed for. To perform new tasks, you’d need to build completely new machines.

But the Universal Turing Machine takes a completely different approach. This machine simulates other machines. It can read a program (the rules of another Turing machine) written on the tape and act as if it were the specialized Turing machine corresponding to that program. The Universal Turing Machine repeats the following process:

- Find the rule corresponding to the current state in the input program

- Modify the tape and change state according to that rule

- Return to step 1 and repeat

Input an addition program and it becomes an adder; input a multiplication program and it becomes a multiplier. You just need to change the software while keeping the hardware the same.

I’ve added an edit button to allow you to modify rules in the Turing machine simulator. Try modifying the bit-inverting Turing machine program to create a program that makes all bits 0 or all bits 1. The program uses CSV strings with the same structure as the control unit table.

Tape

Control Unit

| Current State | Read Symbol | Next State | Write Symbol | Move |

|---|

Significance of the Universal Turing Machine

The most important insight presented by the Universal Turing Machine was the idea that various tasks could be performed by changing only the program while keeping the hardware fixed. Past computational devices had to be designed with separate physical structures for each task—a machine for addition, a machine for multiplication, and so on. But Turing theoretically proved that one universal machine could perform all computational tasks. The key was to change the working method from physical structure to a set of rules supplied to the machine—the program—thereby introducing the conceptual separation of hardware and software.

This idea was a turning point that greatly changed the way people thought at the time, because the concept of treating the logic that a machine performs like data became the starting point of programming today. The development of software concepts like stored-program architecture, compilers, and operating systems was possible because of this theoretical foundation.

Definition of a Computer

Let’s finally define what a computer is. Wikipedia defines a computer as follows:

A computer is a machine that can be programmed to automatically carry out sequences of arithmetic or logical operations (computation).

Interpreting this definition with what we’ve examined, the core of a computer is that it’s a programmable machine. Unlike scissors being defined as “cutting” or cups as “holding,” computers are defined as “capable of performing various calculations through programs.”

This was the identity of that “something lacking” feeling we had in the introduction. The circuits we’ve built so far could only perform specific tasks; they couldn’t perform various tasks through programs. This is precisely the crucial difference between general tools and computers.

Conclusion: From Theory to Reality

The computers we use are essentially implementations of Universal Turing Machines. So how could Turing’s abstract idea be implemented as concrete hardware?

The key is mapping each component of the Turing machine to physical devices. The CPU became the central device handling state transitions and command interpretation functions of the Turing machine, while memory serves as the space for storing programs and data like the tape. The programs we write are essentially rule sets for Turing machines—collections of instructions that define what output should be produced for what input.

But what played a crucial role in this process were precisely the logic gates and circuits we’ve learned about so far. In the next article, we’ll examine in detail how these basic building blocks come together to implement the complex functions of actual computers.

You need to login to leave a comment.